- Home

- E. M. Foner

Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6) Page 9

Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6) Read online

Page 9

The studio audience cheered, and the Grenouthian studio crew all whistled loudly, showing their support of the ambassador. The Stryx spun around a few more times, and then approached the “short” panel. The human ambassador felt herself shrinking in her seat, hoping that Jeeves would take pity and not give her one of the impossible questions. The floating robot stopped directly in front of her.

“Bork!” Jeeves said, not even turning in the direction of the Drazen ambassador. “On the Huravian home world, an order of monks is dedicated to the breeding and education of war dogs. Huravian hounds that forge the strongest connections to individuals are known to return after death in the form of puppies reborn on Huravia. Once a reincarnation is identified, the monks escort it to a Stryx station, and provide the dog with just one item. That item is?”

“I know that one!” Kelly said excitedly. “It’s…”

“Silence!” Jeeves thundered, pointing a menacing pincer in her direction. The audience all booed, and a few even jeered the human ambassador.

“A begging bowl,” Bork answered, as soon as he could be heard. “The emblem on the bowl is a dog looking up at the stars.”

“Exactly,” Jeeves declared, though he said it rather grimly, with none of the enthusiasm with which he’d greeted the prior correct answers. The audience reacted in accordance with the Stryx’s muted response, and other than some polite applause from the few Drazens present, there was silence.

Jeeves floated back over to the other panel and stopped in front of the Verlock, who eyed the Stryx imperturbably.

“Ambassador Srythlan,” Jeeves said.

“Yes?” the Verlock replied ponderously.

“On the Farling world of Sixteen, there is a naturally occurring compound…”

“Quadhexseptiumsylleucyglutamyleucine,” the Verlock interrupted Jeeves, shocking everyone present with the rapid-fire syllables.

“Winner!” Jeeves practically screamed. “Winner, winner, winner. Oh, the wonders biologicals are showing us today. Now let’s ask a question of the new kid on the block, the creator of this show, the inheritor of the Kasilian treasure, and the recent Carnival Queen. The incomparable, Ambassador Kelly McAllister!”

Kelly began to blush halfway through the introduction, though strangely enough, it made her feel cold rather than warm. And when Jeeves finished his build-up, the studio audience remained dead silent. Kelly kicked herself for making her family and friends stay at home. Jeeves approached slowly, allowing the silence to stretch on until it became almost painful.

“Libby!” Kelly subvoced urgently. “What’s wrong with Jeeves? Libby? Hello? Gryph?”

It was the first time in fifteen years on the station that Kelly had called out and not received an answer. Suddenly she remembered that Jeeves was jamming their implants to prevent cheating.

“I’ve changed the rules a little to make your show more interesting,” Jeeves said, menace dripping from each syllable. “Answer correctly, and you’ll go on to the direct questioning round. Get it wrong, and I promise you a painless transformation into a frog. For all of your marbles, the Oxus Civilization belongs to what historical age on Earth?”

The EarthCent ambassador froze, the threat ringing in her ears. She was sure she knew the answer but she couldn’t think, the words just wouldn’t come out. She turned desperately to Bork, who was hiding his lips from the Stryx behind a hand and mouthing something at her. Brown? Browse? Brawn? It was on the tip of her tongue. Bra?

Kelly looked down and saw that she was wearing nothing but a bra and panties. Bork leered, and the floating holo-cameras moved in for a close-up as she screamed.

“Five seconds!” Jeeves stated maliciously.

“Kelly,” Joe said. “It’s all right, I’m here.”

“Four! Three!”

“Joe,” she sobbed in relief, craning her head to locate him. “What age was the Oxus Civilization?”

“Two! One!”

The crowd screamed for blood, and her face began to turn wet and hot, the beginning of her transformation to amphibian form.

“Kelly! Wake up,” her husband shook her shoulder. “You’re having another nightmare about the show!”

“Nightmare?” Kelly asked, sitting up in bed. She pushed away Beowulf, who had covered her face and hair with dog slobber in a futile attempt to rouse her.

“I tried to wake you up, but you kept asking me a question about the Oxus Civilization.”

“Bronze Age!” Kelly exclaimed. “Why couldn’t I remember that a minute ago? Jeeves was going to turn me into a frog.”

“And I was going to say you’ve been spending too much time trying to come up with a plan for your show, but now I’m worried you’re spending too much time reading children’s books.” Joe hugged his wife the best he could while sitting in bed, and began patting her on the back like a child. “The Stryx don’t turn people into frogs. That’s a fairy tale thing.”

“All the other ambassadors knew the answers to the questions Jeeves asked, and most of them were really hard,” Kelly recounted. “Then he looked right at me and asked a question about Huravian reincarnation, but it was for Bork.”

“What was Jeeves doing on the show in the first place?” Joe asked.

“To keep everybody from cheating,” Kelly explained. “When he started acting funny, I tried to contact Libby or Gryph, but he blocked me. And then the whole galaxy saw me in my underwear. It was horrible.”

“Listen, Kel. You know I’ll support you in anything you do, but I think that maybe your subconscious is trying to tell you something.”

“That I’m stupid?” Kelly sat up a little straighter and pushed her husband away. “Is that your interpretation, that I have an inferiority complex? Next time I have a bad dream I’m asking Dring or Libby to do the psychoanalyzing.”

“I don’t think you have an inferiority complex,” Joe protested, trying to get Kelly to turn her head back to look at him. “I think it’s a performance anxiety dream. You’re great at standing up and speaking your mind when you have to, and I’ve even seen you give a couple of decent speeches, but you’ve never been an actor, a performer. It’s not that I think you’re trying to compete with Aisha, but it does seem that in all of the show ideas you come up with, you cast yourself in the role of a participant, or even the master of ceremonies.”

“I was both in this one,” Kelly admitted. “I completely flubbed my opening, but I don’t remember the details now.”

“You don’t see the Grenouthian ambassador appearing on the shows he helps develop,” Joe reasoned. “If things are really so slow around the embassy that you need another job, talk to Clive and tell him to start sending more of the aliens who contact EarthCent Intelligence your way.”

“Maybe you’re right,” Kelly replied, and let out a long sigh. “I do keep trying to give myself a part, and perhaps I am a little jealous of Aisha. I’m going to start auditioning human moderators so I don’t have to participate on camera.”

That’ll be a welcome relief, Beowulf thought, as he padded back to Dorothy’s room where he had claimed most of the floor space. A growing dog can only take so many of these middle-of-the-night interruptions.

Ten

“Thank you again for not inviting your Mom,” Mist told Dorothy. “It wouldn’t have been much fun for everybody if we had two ambassadors, and Gwendolyn would have been disappointed if I didn’t ask her.”

“It’s not a Parents Day, it’s a Career Day. It’s just for us grown-up kids,” Dorothy explained. “And when I was little and Mom came to Parents Day, it didn’t go that well.”

“And when I was young, I never got to invite anybody for Parents Day,” Metoo added, hoping that his own history would reassure Mist in case she felt left out. “You can invite anybody you want for Career Day, even sentients from different species. But I found out there’s never been Stryx for Career Day before, so I asked Jeeves.”

“It might have been better to ask somebody else,” Dorothy said. “It’s

not as if biologicals who study really hard can grow up to get work as Stryx.”

“Shhh. Gwendolyn’s here,” Mist said to her friends. The class, ranging from ages twelve to fourteen, were lounging around on the grass in the presentations area, propping themselves partially upright with pillows and beanbags. The number of Stryx who participated in classes began to fall off around the age of ten, but those who could visit Union Station on short notice still came for the school’s special events to keep up with their human friends. There weren’t any parents present.

“Hello, students,” Gwendolyn said, as she moved uncertainly to the front of the group. “I don’t see a teacher here. Should I just begin?”

“You’re the first today,” answered a boy who was sitting cross-legged near the front. “You get to make your own rules on Career Day, but you can’t go over ten minutes with the questions and answers. Your sponsor should introduce you.”

“I was about to, Maximilian, before you interrupted,” Mist said, clambering to her feet. The class was just getting to the age where the boys and girls took great satisfaction in telling one another how they should act. “I invited my sister Gwendolyn to talk about her work. She’s the Gem Ambassador on Union Station.”

The children applauded politely.

“Well, this sounds fun,” the clone said. “Should I talk about being an ambassador?”

“We had one of those already,” a girl called out. “It was yucky. Have you done anything else?”

“We’re grown-ups now, Bekka,” Dorothy told the girl. “This ambassador isn’t going to make us play games.”

“I don’t have to talk about being an ambassador,” Gwendolyn said. “I’ve only been one for a couple of years and I usually don’t know what I’m doing. I used to be a waitress. Do you want to hear about that?”

“Yes!” Bekka answered. “My sister is a waitress and she makes oodles of creds in tips.”

Gwendolyn exchanged a significant look with Mist, communicating through a mix of body language, empathy, and a bit of clone telepathy, to make sure the subject was alright with her. Mist shrugged, a sign even Dorothy could understand.

“To give you a little background, when I was just about your age, I started working on the Gem crèche world with babies,” Gwendolyn began. “But the supervisors said that I was too sentimental to work with the little ones, so they sent me for waitress training.”

“Do you need training to be a waitress?” a different girl asked. “I thought you just had to memorize the specials and stuff.”

“You need training for all jobs,” the Gem replied. “Sometimes it’s formal training, like in a school, and sometimes it’s on-the-job.”

“But you get paid for on-the-job training, right?” Bekka asked.

“On Union Station you do,” Gwendolyn replied. “That’s because the Stryx have labor laws for the multi-species decks, so if your own species wasn’t willing to pay, you could usually find a better job just a lift tube ride away.”

“But the Gem Empire didn’t pay anybody for anything,” Mist added.

“Well, not in the way business works on the station,” Gwendolyn said, clarifying Mist’s words. “In the old Gem Empire, everybody got a job and everybody had to work. If you didn’t show up for work, you couldn’t go to the dining halls or the clothing warehouses. The Gem who were in charge, the elites, got better rooms, and access to better dining halls and better warehouses, but nobody got paid in creds. We didn’t even have our own form of money.”

“Weird!” said the boy sitting up front. “We know that barter is better, but how can you save for retirement or travel without money?”

“There wasn’t any retirement, really,” Gwendolyn explained. “And there wasn’t any stuff to buy either, just the places you were allowed to go and get stuff, depending on your job.”

“And you didn’t get an allowance?” a girl asked incredulously. “How could you go out with your friends, or rent flying wings? Were your parents that mean?”

“Lydia!” Dorothy scolded the girl. “Weren’t you listening when Libby introduced Mist to the class? They’re clones.”

“So?” Lydia responded in a huff. “If I was a clone, I’d still give my daughter an allowance.”

“You’re both right, so please don’t argue,” Gwendolyn interjected. “Dorothy is correct that we don’t have parents because we’re all sisters, and Lydia is correct that the older sisters act as parents for the younger. But when you’re just a child in crèche, you don’t understand that the food from the dining hall and the clothes from the warehouse are actually gifts from your older sisters. It’s just the way things work, so it seems as if the Empire is your mother. Humans have parents or guardians who take care of you when you’re too young to take care of yourself, so you form family bonds with them. Gem children were taught that everything came from the Empire, and we were prohibited from making friends with anybody outside of our caste.”

“So you never made any tips as a waitress?” Bekka asked, getting to the crux of the matter.

“No,” Gwendolyn replied. “When I started, we didn’t even get to eat the same food as the upper castes we served, because our meals were from a different self-service dining hall.”

“No wonder the waitresses led the revolution,” Bekka exclaimed. “If my sister had to wait on people who got better food than her and never tipped, she would have put sleeping drugs in their food too!”

“You might not believe me, but the job was better before the whole Empire shifted to the all-in-one nutrition drink,” Gwendolyn told them. “After that, all we did was count people and bring out glasses on a tray. At least back when they were ordering fancy food, I could smell it, and imagine that one day somebody might leave an uneaten portion on the plate. Without different types of food to remember and describe to patrons, waitressing was incredibly boring. The best thing is if you can find work that’s challenging.”

“That’s what Libby says,” Maximilian observed. “I think it’s around ten minutes,” he added.

“I was about to tell her that,” Mist exclaimed in annoyance.

“Thank you for having me,” Gwendolyn concluded, wondering why Kelly had warned her against ever participating in a Stryx school event. The children applauded enthusiastically, and Mist sat up very straight, sharing in her sister’s success.

“I’m next,” Metoo called out, rising up and floating above the other students. “I mean, Jeeves is next. He’s my Career Day display.”

“Thank you, Metoo,” Jeeves bellowed, zooming up to the front at break-neck speed the moment the introduction was completed. Metoo settled back into his place next to Dorothy. “As the first Stryx to attend Libby’s experimental school, I’m honored to be invited back for this special event.”

“But you don’t have to work,” a boy in the back objected. “You’re Stryx.”

“You don’t have to work either,” Jeeves retorted. “You can run away from home and join the Wanderers. Oops, Libby just told me to say I didn’t mean that. Besides, I started working when I was younger than you. All Stryx do.”

“But we can’t hope to be chosen to rule a whole species as High Priest, like Metoo,” a girl pointed out.

“Do you think that’s the only career path open to Stryx?” Jeeves parried. “I’ll even let you choose which one of my careers to talk about. I’ve been the chief troubleshooter for the Eemas dating service, an auctioneer, and I’m a member of Galaxy Watch.”

“You worked for Eemas?” Bekka asked. “I want to hear about that.”

“What’s Galaxy Watch?” Maximilian demanded.

“Galaxy Watch consists of a heavily armed and dangerous group of intrepid warrior AI who defend the tunnel network from—what do you mean the subject is out of bounds?” Jeeves trailed off in complaint. “Libby told me to stop exposing her censorship and to talk about the dating service.”

“Wow, Jeeves is really cool,” said the boy sitting behind Metoo, nudging the robot.

“Can you find me a boy who doesn’t smell funny?” a girl called out, leading the other girls in the class to collapse into giggles.

“If I still worked for Eemas, I could find you a boy who smelled any way you like,” Jeeves replied. “It’s one of the gazillions of factors we considered when making introductions.”

“Gazillions?” Dorothy asked skeptically. “The way my mom described her dates, it sounded more like Eemas was picking guys at random. They weren’t even all human.”

“The ambassador was part of the special remedial dating program,” Jeeves explained. “All of the other species on the station sign up with a dating service to find their best match, but some humans can’t coherently describe what they want for breakfast, much less for the rest of their lives. So rather than wasting the ideal match for humans on the first date and risking a rejection, we try to use the early dates as a training program.”

“That sounds like the sort of thing Libby would do,” Bekka commented.

“Does a dating service troubleshooter ever get to shoot anybody?” Maximilian asked.

Rather than replying with words, Jeeves projected a hologram of himself mounted on the hull of the Nova, firing an energy beam weapon at a Sharf cabin cruiser and scoring a direct hit on the propulsion system. The boys in the class all whooped and shouted. That hologram was immediately replaced by another, this one showing a full-fledged space battle between small robots and some type of massive ship none of the kids recognized. The caption “Galaxy Watch” flashed at the bottom, but the projection was quickly extinguished.

“Oops, how did that get onto my dating service reel?” Jeeves said innocently, after the boys calmed down. “I’d show you more, but you know who is you know what.”

“Did any of the dates Eemas sent people on result in marriages instead of battles?” a fourteen-year-old girl in the back asked icily.

“Practically all of them,” Jeeves replied. “The Eemas service had a success rate near a hundred percent before humans came to the station, but you people are tough. I got the job as troubleshooter because after attending this school, I was better at predicting human behavior at the individual level than the other Stryx. When things weren’t working out and I was called in, I’d start knocking heads together,” he concluded on a macho note.

Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16)

Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16) Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18)

Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18) Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4)

Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4) Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11)

Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11) Assisted Living

Assisted Living Con Living

Con Living Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network

Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network Career Night on Union Station

Career Night on Union Station Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15)

Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15) Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9)

Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9) Soup Night on Union Station

Soup Night on Union Station Human Test

Human Test Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4)

Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4) Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12)

Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12) Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10)

Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10) Turing Test

Turing Test Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2)

Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2) Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6)

Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6) Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7)

Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7) Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13)

Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13) LARP Night on Union Station

LARP Night on Union Station Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5)

Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5) LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14)

LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14) Book Night on Union Station

Book Night on Union Station High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3)

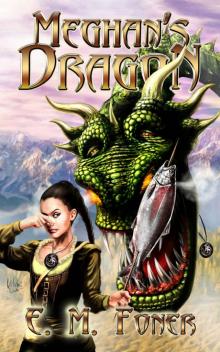

High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3) Meghan's Dragon

Meghan's Dragon Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2)

Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2) Guest Night on Union Station

Guest Night on Union Station Date Night on Union Station

Date Night on Union Station