- Home

- E. M. Foner

High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3) Page 7

High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3) Read online

Page 7

Kelly sat back, feeling that she had won the first point in a match, and tried to figure out the best way to bring up returning the High Priest’s necklace, which featured a finger length crystal rod as a pendant. By an unspoken mutual decision, everyone waited patiently for Yeafah to come to a decision that was obviously painful for her. Suddenly, the High Priest’s eyes shone with a light that forced the humans to look away, and even caused Dring to blink up the filters he engaged when welding or surfing too close to stars.

“If it wouldn’t be too much of a burden for you, may I request transportation to Union Station so I can arrange for the disposal of our unwanted items there?” Yeafah asked hopefully. “Their bulk is less than you might think since we spent all of our Stryx creds and bullion on restoring the surface of Kasil thousands of years ago.”

“That would be no burden at all,” Jeeves answered immediately, before Kelly even had a chance to open her mouth. “After you make the necessary arrangements, we will provide transport for your treasure, but I advise moving quickly. The expectation of our opening your tunnel exit has so far prevented ships from attempting to jump into your system, especially with the edge of the Darkness growing so near, but greed will eventually overcome fear.”

“Wait a second,” Kelly protested. “I thought we wanted the Kasilians to keep their stuff. And doesn’t this just shift the riot to Union Station?”

“The decision to divest has already been taken,” the High Priest reiterated firmly. “Would you rather we threw all of our museum collections into the sea?”

“Union Station can take care of itself,” Jeeves added in support of Yeafah. “From what I know of humans, you should be more worried about complaints from your merchants that giving away shiploads of treasures will interfere with the functioning of the local markets.”

“He’s right about that,” Joe interjected. “I’ve seen something similar happen after the sack of a royal treasury in war. When soldiers fill their pockets with gold and jewels, all of a sudden the price of a beer or a bed goes through the roof. It can wreak havoc on an economy, and the hard-working people who didn’t load up on loot wake up to find they can’t afford a loaf of bread.”

“Since I have no experience in your galactic economy, I promise to be guided by your counsel when we reach the station. But I am still the spiritual leader here, although my term is drawing to a close. Before we leave, I shall officiate at the initiation ceremony of your comrade who has asked to join our priesthood, and I hope you will all attend,” the High Priest concluded, and rising from her seat, exited the room.

“She can’t mean Becky!” Kelly cried at Mary, who also appeared quite startled at Yeafah’s pronouncement.

“I don’t think so,” Mary shook her head. “No, it can’t be. Becky told me just this morning that the local priests were waiting for the High Priest to reverse the effects of the vision drug. Disassociation, they called it.”

“Maybe some human took a crazy gamble and jumped into the system despite the odds,” Joe speculated. “I knew plenty of guys who would have thought nothing of joining the priesthood for an inside track to the kind of treasure they’re giving away.”

“No ships have jumped into this system since we arrived, or for a very long time beforehand,” Jeeves cut the speculation short. “And the members of the Kasilian priesthood must be highly proficient in both mathematics and astronomical observation at wavelengths that humans cannot detect without instrumentation.”

“So it’s not Shaun,” Mary said, letting her breath out in relief.

“Are you leaving us, Dring?” Kelly asked the other half of her Victorian book club.

“No, I have my own path to follow,” the Maker replied, sounding puzzled. “Process of elimination suggests just two possible candidates.”

As if in answer to Dring’s observation, Metoo floated in the door, draped in a brown toga that dragged on the floor.

Eight

“How am I going to explain to Stryx Farth that his son Metoo has joined the priesthood of a doomsday cult and remained behind on a suicide planet?” Kelly asked Libby, after she finally caught up with urgent correspondence when the delegation returned to Union Station.

“It will be a good experience for him,” Libby told her. “I hope he decides to return to our school before his impressionable age passes, but it was already clear that he couldn’t follow Dorothy around like a shadow forever. Besides, you don’t have to explain anything. Farth knew about Metoo’s decision before you did, and he heartily approves.”

“But the Kasilians are just sitting there waiting for their world to come to an end,” Kelly protested. “All they do is watch the Darkness, as if that makes any sense.”

“I think it’s very spiritual,” Libby replied. “There are times I wish my Jeeves took a little more interest in the unknowable and a little less interest in practical jokes.”

“Some of the artwork they’re giving away is priceless,” Kelly changed the subject. “Bork already got in touch to tell me there are Drazen temple panels in the Kasilian catalog that were thought to be lost ages ago. Czeros absolutely flipped out over something that looked to me like an oversized straw hat. He said it could be the only example of a Frunge treaty weaving left in existence. The Kasilians even have a complete image library of Gem from the days before cloning, not that the Gem are interested in them.”

“The Kasilians were a very acquisitive species in their days of empire, and it seems they pruned their collection of artifacts to the most valuable pieces before retreating to their home world. I know we didn’t have time to go over the history of Kasil before you left, but now that you’ve been there, would you believe their world was once a wasteland half-covered by metal-encased super-cities? You couldn’t go outside without an environmental suit, and the flora and fauna were practically wiped out by millions of years of industrialization.”

“It looked to me more like the world that time forgot,” Kelly replied doubtfully. “Other than some astronomical observatories and gadgets, they appeared to be at the same level as Earth a couple thousand years ago.”

“It shows what you can do, or undo, with enough money and time,” Libby expanded on her thesis. “When the Kasilians began returning to their home world to wait for the end, they embraced the back-to-nature approach you see today. Most of the wealth they had accumulated over millions of years of spacefaring went into restoring Kasil. They were able to re-import strains of the original flora and fauna from their colony worlds, but the cost of remediation was stupendous. Even today you find merchant families among the Dollnicks whose fortunes date back to trash-hauling contracts for the Kasilian clean-up.”

“But why would they spend a fortune fixing up a planet just to have it destroyed?” Kelly asked in frustration. “No matter how I look at it, the whole thing doesn’t make sense. Dring told me that the Kasilians were the galaxy’s worst pessimists, and that the only things they believed in were wealth and astronomical observations. Then some prophet or mathematician comes along and proves that their home world is on a collision course with destruction some ten thousand years in the future. So why did they decide to give up all of their technology and go home to wait for species death? Why didn’t they keep their wealth and their colonies and strip whatever was left of value from Kasil?”

“It was their unanimous choice,” Libby replied. “Some races can reach a species consensus, as if they share a group mind. I can’t tell you with any certainty why the Kasilians chose the path they did, though it’s common for biologicals to wash the corpses of their dead before burial, so perhaps there’s a parallel. I can only remind you that for all of their faults, the species you have encountered on Union Station are the stable ones. The Stryx have witnessed the rise and fall of uncounted sentient species, some who never leave their planet of birth and others who spread across the galaxy and beyond. At a certain point in their development, many intelligent species find that their evolution has left them spiritually, or you migh

t say, psychologically unsuited to their place in the universe. Some find peace by going home, others by stepping back from technology or breaking all ties with their home world and starting anew. Unfortunately, a large proportion of biologicals simply reach a peak and then go into decline, often to the point of extinction.”

“It looks to me like the Kasilians have doubled-down on extinction,” Kelly said sourly. “Even if Kasil isn’t eaten by their precious Darkness, the entire population of the planet wouldn’t fill half of Union Station.”

“Knock, knock?” Aisha called from the door, peering around the corner, as was her habit.

“Come in, come in,” Kelly replied in relief. A nice chat with the naïve intern would be a welcome break from discussing the extinction of a species. “How was the fundraiser? Did Paul treat you well?”

Aisha looked a bit flustered for a moment, which in combination with her cheap coveralls, made her look like a lost schoolgirl who was late for her part-time service job. Kelly resolved on the spot to send her shopping with Donna, who had years of experience getting her own fashion-indifferent daughters to dress like adults.

“The fundraiser was very strange,” Aisha finally replied. “I spoke a little with the Drazen and Frunge ambassadors, who were very friendly, but they also seemed to be making fun of us. They put on some sort of skit they called an EarthCent Ambassador game, and it drew quite an audience. Then the Vergallian ambassador tried to, uh, to befriend Paul, and I’m afraid I was a little rude to her.”

“I know what kind of friends the Vergallian women try to make of human men. Pets is a better description,” Kelly remarked scornfully. To avoid explaining the Drazen and Frunge theatrical production, she resorted to a little teasing. “And did Paul behave himself as a gentleman?”

“Why didn’t you tell me he is dating Blythe?” Aisha asked suddenly while sticking out her bottom lip, the closest thing to a confrontational expression Kelly had ever seen on her intern. “It was very embarrassing to have her walk into the kitchen when I was alone with Paul after dinner. It made me feel like a pracanda mahila, a wanton woman.”

“Nobody mentioned that Paul and Blythe are a couple?” Kelly asked in surprise, not noticing Aisha’s wince at the term. “I suppose we’re all so used to them dating that we take it for granted that everybody knows, and she was probably away on business from the time you arrived on the station. But to tell you a secret,” Kelly lowered her voice conspiratorially, “I’m not so sure that she’s good for Paul. He’s always let her boss him around a little too much.”

“Really?” Aisha perked up immediately. “I was surprised that they aren’t even engaged after dating for three years. It seems like an awfully long time to wait for people who love each other.”

“Joe and I got married on our first date,” Kelly replied instantly, as it wasn’t something she often had the chance to boast about. “Of course, I was a bit tipsy. But the fundraiser and one dinner with Paul didn’t take up your whole week. What else did I miss?”

“Well,” Aisha replied, thinking to herself that it wasn’t just one dinner, “I took your weekly meeting with the Earth merchants from the Shuk and the guilds this morning. They had all heard about the Kasilian offer by then, and word was already out that the High Priest was accompanying you back to the station to dispose of Kasil’s wealth here.”

“Libby?” Kelly inquired, turning her eyes upward. “How is it that everybody knew we were coming back with Yeafah when the Kasilian’s only communications technology relies on visions?”

“We had to tell all of the ship captains waiting at the tunnel entrance something or they would have clogged up the shipping lanes forever,” Libby replied. “Most of them chose to come directly to the station, and I have no doubt that Joe has a few new campers.”

“What did the merchants who attended the meeting have to say?” Kelly asked, looking back to Aisha.

“They all had different opinions about how the Kasilians dumping their wealth on the station would affect business, but as I understood it, the main problem is uncertainty,” Aisha reported. “Because it’s something they’ve never experienced, they don’t know how to prepare for it. They feel like they have no control over the situation. I’m afraid many of them blame you and EarthCent for bringing the problem here rather than keeping it on Kasil.”

“Our merchants are a tough bunch,” Kelly said sympathetically. “I hope they weren’t too hard on you.”

“It was a little scary at first,” Aisha admitted. “But then I told them the story about how my family’s business changed after the elevators opened, and super-cheap textiles from the robotic orbital factories around the galaxy flooded the market. My mother convinced my father to let the old business go and to refocus on hand-made clothing for weddings and the luxury market. It was hard for the first few years, but now they are starting to do well for the first time in their lives. One woman who owns a clothing boutique on the retail deck even asked me for their contact information.”

“If the merchants like you that much, maybe you should take over the weekly meetings,” Kelly offered with a smile.

“What will the High Priest do now?” Aisha asked, emboldened by the praise and a week of working on her own.

The ambassador was surprised and pleased that Aisha had finally asked her a question without asking for permission. Kelly had been considering a clandestine course of aggressiveness training for her overly polite intern, such as a trumped up undercover assignment working with the Hadads in the Shuk or with Donna’s girls at InstaSitter. The girl was obviously intelligent and always looked like she had something to say, but she rarely opened her mouth unless Kelly asked her a question. Maybe she was starting to come around on her own.

“I wish I could tell you,” Kelly replied glumly. “The whole trip was something of a disaster from my point of view. Did you know that Metoo joined the Kasilian priesthood and stayed behind? I don’t think it’s really hit Dorothy yet, but don’t be surprised if you see her moping around the house. I only hope that the Cricks stay around a while longer, because without Kevin, the poor girl would have lost all of her admirers.”

“The High Priest didn’t say anything about his intentions?” Aisha followed up, displaying the ability to remain focused on the point.

“She, not he,” Kelly responded. “Her name is Yeafah. I’m not sure it’s even a religion, exactly, despite the priesthood. It’s just the closest translation to English. Dring explained that some species have concepts for which there simply isn’t an equivalent in human experience, so the translation implants just pick something that’s related.”

“So did Yeafah say anything about her intentions?” Aisha persisted stubbornly.

“She mainly talked about fish and birds,” Kelly admitted. “The Kasilians see the restoration of their planet’s natural cycles that were lost in their hyper-industrial age as their great achievement. But the way she tells the stories, they all end in death. The fish return home to their streams and die. The birds fly around the world with the seasons and die. The great herds circle the plains and die. The forest creatures—you get the picture.”

“But that’s Samsara, the circle of life,” Aisha protested. “With death comes rebirth, it’s never-ending.”

“Not in the Kasilian version,” Kelly retorted grimly. “Dring explained that their whole system, whether you call it religion or government, was founded on the discovery that their star system is doomed. Astronomical observations have been the uniting passion of Kasilians from time immemorial, perhaps because Kasil has no moon and their location in the galaxy makes their night sky brilliant. You know that on Earth there are amateur astronomers who hunt for comets?”

“Yes,” Aisha replied briefly, wondering if there was a point to her superior’s discursion.

“On Kasil, all adults spend several hours a night studying the heavens, and they took the tradition with them when they began colonizing other worlds. But it turns out that stargazing was their only like

able characteristic. They were rapacious in business, fought wars amongst themselves to acquire property and slaves, and only tolerated other species when they could see an economic advantage. They were major players on the galactic stage for a few million years, but then they went into sharp decline, a sort of collective mental break-down, as Dring described it.”

“But what does this have to do with their world being doomed?” Aisha demanded with uncharacteristic impatience.

“I’m getting there,” Kelly replied, amused that Aisha could have changed so much in just a week. “A Kasilian scientist who became known as Prophet Nabay spotted a sort of a gravitational distortion moving through space, on a course that would eventually intercept their star system. Of course, space is so vast that even large objects like black holes and stars can pass through occupied systems, with the main danger being from gravitational effects. But Nabay showed that this distortion, which the Kasilians call the Darkness, was something else altogether. It’s more than large enough to swallow up entire star systems, and where it traveled, it left empty space in its wake.”

“What do the Stryx say about it?” Aisha asked.

“I told Joe to ask Jeeves and then explain it to me,” Kelly answered. “He said that they call it Darkness because it’s made of stuff that you can’t see, but the Kasilians can detect its path indirectly because it bends the light from other stars. Joe said that human science hasn’t developed the models to describe Darkness anymore than we can understand how the tunnels or jump engines work. He also said that we’ve known for almost a century that the universe mainly consists of matter and energy we can’t see, and that this is some of it.”

“Can the Stryx fix it?” Aisha couldn’t help asking.

“They aren’t omnipotent,” Kelly replied. “Saving the Kasilians isn’t a problem if the Kasilians will only go along with it. There are so few of them at this point that they would all fit on a Stryx station like this one, with room for twice as many more. Jeeves said that given enough time, the Stryx could have used gravitational towing to move Kasil to a new star system. But it’s extremely complicated to do with a world that’s occupied, because you have to provide heat and light on the trip, essentially an artificial sun. The Stryx could have done it if they started when Nabay first discovered the Darkness, but there isn’t anywhere near enough time remaining.”

Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16)

Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16) Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18)

Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18) Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4)

Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4) Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11)

Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11) Assisted Living

Assisted Living Con Living

Con Living Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network

Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network Career Night on Union Station

Career Night on Union Station Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15)

Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15) Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9)

Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9) Soup Night on Union Station

Soup Night on Union Station Human Test

Human Test Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4)

Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4) Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12)

Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12) Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10)

Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10) Turing Test

Turing Test Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2)

Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2) Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6)

Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6) Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7)

Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7) Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13)

Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13) LARP Night on Union Station

LARP Night on Union Station Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5)

Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5) LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14)

LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14) Book Night on Union Station

Book Night on Union Station High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3)

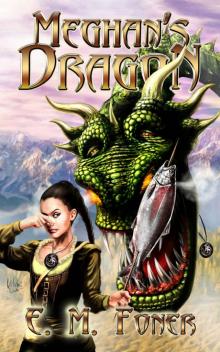

High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3) Meghan's Dragon

Meghan's Dragon Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2)

Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2) Guest Night on Union Station

Guest Night on Union Station Date Night on Union Station

Date Night on Union Station