- Home

- E. M. Foner

Date Night on Union Station Page 2

Date Night on Union Station Read online

Page 2

But other than the occasional indecipherable communication, EarthCent offered no guidance for employees in the field. It was more like an employment agency for an independent diplomatic service. In the last fifteen years, Kelly had received the drunken confidences of many an EarthCent diplomat at various embassy and consul functions, and the only explicit instruction any of them had received from EarthCent was in the initiation oath, to do their best for humanity.

So here she was, two years into her tour as Earth’s top diplomat on the most important space station in the sector, and Kelly still wasn’t sure about the boundaries of her job. When aliens contacted her office looking for information about Earth, she tried to answer their questions and generally point them in the right direction. When invitations to diplomatic events arrived, she dutifully strapped on her high heels, slipped on her black dress, and checked with Libby to make sure that the atmosphere at the party wouldn’t dissolve her lungs or melt her skin.

Kelly used to believe she was going through an extended trial period, after which EarthCent or the Stryx would cue her in on the big picture. Recently, she was beginning to suspect there was no overarching strategy. Instead, Gryph often questioned her about the misbehavior of humans on the regional galactic scene, and more than once she found her responses had been acted on as if she had the final say in all things human related. It was definitely a little humbling, and when people asked her what she did for work, she had to restrain herself from answering, “I’m sort of responsible for humanity within a couple hundred light years.” The consul’s job apparently encompassed the judicial, executive and legislative branches all in one, and her salary didn’t quite cover her living expenses.

authorized negotiations stop

Did that mean she was authorized to negotiate with these Belugians she’d never heard of before today, or was the message referring to some third party? All she’d been able to find out was that Belugians referred to a chartered mutual company that included members from various species. How was she to locate the contract holders, much less negotiate, when she didn’t know what they wanted or what she could offer? Kelly’s thoughts were interrupted and she jumped in her chair as a hot hand clasped her bare shoulder and spun her stool away from the bar.

“Long red hair, black dress, green eyes,” a raspy baritone pronounced. “Barkeep, I’ll have what she’s having.”

Kelly fought back the urge to stand up and leave. She hated when strange men put their hands on her without so much as a how-do-you-do, but she had promised Donna and the girls to spend at least a half hour with each date to give the man a chance. The service was so expensive, she intended to think of the dates as the best paying work she would ever have in her life. Instead of stalking out or throwing her ice water in his face, she reached up and removed his hand from her bare shoulder, returning it to him with a tight smile.

“I’m Kelly. You must be Branch,” she said, trying not to sound downright hostile as she surveyed his tall, dark, bearded form. Not unhandsome, she decided, in a piratical sort of way. But way too aggressive and overconfident, and probably one of those guys who figures conversation is a waste of time.

“Branch I am,” he replied, taking her first salvo in stride and settling onto the stool next to her. “Is this your first Eemas hook-up?”

“Actually, it is.” She regarded him quizzically, pondering his choice of words. “Did I do something to give it away?”

“Oh, no,” he laughed. “I just wondered, since it’s the first time I’ve done anything like this myself. Never needed help meeting ladies,” he concluded with a wink and a friendly leer.

“So what possessed you to shell out for tonight?” she inquired wryly.

“Shell out?” Branch appeared puzzled for a moment as he ran his eyes over her exposed skin, as if looking for seams. “Oh, you mean pay. No, I didn’t pay, I just got an invitation from this Eemas thing when we docked a few hours ago. I was going to visit a hostess house with the rest of the crew, kind of a tradition with sailors, you know, but when I saw your picture, I had to come.”

“Picture? You got a picture?” Kelly almost squeaked in aggravation. “And you didn’t have to pay?”

“Easy, Red, I just said that, didn’t I?” Branch took the ice water the bartender brought him and drained it in one gulp. An expression that combined amusement with distaste fled across his features, and he shook his head in mock despair as he returned the empty glass to the bar. “You really do know how to party, don’t you?” he commented, then continued without giving her a chance to respond. “So, shall we go back to your quarters or would you rather we rent a room? I’m feeling generous so it’s my treat.”

“What? Wait!” Kelly sputtered as Branch rose and started for the exit, as if her only logical option was to follow after him like a lost puppy. “What do you think this is? I mean, I came for a date!”

“A date?” Branch hesitated and stepped back to the bar. He fingered the wedge of lemon on his empty water glass and took a long look at the tray of sliced fruit on the bartending station. Then he shook his head and said, “Oh, a date! I can do that, sure. Would a half hour be enough?”

“A half hour would be perfect,” Kelly answered with a cold smile, and brought up a digital stopwatch display in the corner of her eye. Then she had a pleasant thought and advanced the countdown from thirty minutes to twenty-six, to account for her last four minutes on dating duty.

“Well, would you like something to eat, or should we just get some real drinks and talk?” Branch asked, settling back onto his stool with the ease of a veteran campaigner.

“Talking could be nice,” Kelly replied, swirling the ice in her glass for the reassuring tinkling sound it made. “You mentioned you just got in, so what brings you to Union Station?”

“Union has the best cross-galactic tunnel rates on this side of the lens,” he quoted from the repeating welcome message that greeted all approaching ships and signaled to the bartender. “And if you can keep a secret, we’re picking up some obsolete disintegrator projectors, good war surplus stuff left over from the Yeridum/Mudirey wars.”

“I’ve never heard of either—wait, that sounded like the same name spelled backwards,” Kelly ventured. She had always been proud of her aptitude for pattern recognition and ability with numbers, and she secretly believed that these were the talents for which the Stryx had plucked her out of obscurity halfway through her sophomore year in university for her first posting as a junior diplomatic aide.

The arrival of the bartender made a break in the flow of the conversation, and Kelly ordered a screwdriver, while Branch asked for a Divverflip. “One screwdriver, one Drazen Divverflip, coming up,” the bartender repeated the order and favored Kelly with a curious look of appraisal before retreating towards the collection of bottles at the center of the long bar.

“Of course, that’s why it’s also called the Mirror War,” Branch continued their conversation with just the slightest hint of condescension, not unusual from a man discovering that a woman lacks his enthusiasm for archaic conflicts. “The Yeridum accidentally broke into a parallel universe, but you aren’t really interested in all that.” He cut himself off to Kelly’s surprise, just as her features were beginning to go slack. Maybe he wasn’t that insensitive after all, she thought, or maybe he’s just that desperate.

“Are you some kind of pirate that you’re in the market for disintegrator weapons?” Kelly joked, or at least she hoped it was a joke.

“Not these days,” Branch replied and rubbed the side of his nose significantly while glancing around the lounge to see if anyone was obviously eavesdropping. Everybody knew that there was no true privacy on the station because the Stryx had built the place and probably kept every molecule under surveillance, but the robots were also famous for minding their own business and letting the biologicals have at it as long as they followed the local rules.

“Disintegrator projectors were lousy weapons since they work so slowly and most targets aren�

��t going to stay still long enough for them to do much damage,” he continued. “But they’re useful for peeling surface layers off a planet from space if you have enough power. A great tool for terraforming and such.”

The bartender returned with Kelly’s screwdriver and a smoking purple concoction which looked like toxic waste that had been remediated with food dye. Kelly took a sip of her screwdriver, which was excellent, and received a wink from the bartender who waited around to watch Branch sample his Divverflip. Branch tipped the glass up for a taste, and then drained half the contents at a go. The two males exchanged approving head nods, and then the bartender moved off to greet new patrons.

“I’ve always been interested in terraforming,” Kelly fibbed as she relaxed into bad date mode, thinking this was a subject that would get them painlessly through the remaining twenty something minutes. Besides, she found it paid to keep her ears open, as Libby was fond of hinting that human knowledge was limited more by laziness than by storage capacity. “Is that what you do?”

Branch considered the question and scratched absently behind his ear. “Well, it’s not really terraforming if you stop halfway through, more like strip mining. But what’s wrong now?” he demanded in annoyance, seeing that Kelly had turned white and was staring behind his head.

“What was THAT?” she asked in a hollow voice, as a feeling of dread climbed up her chest.

“What was what?” Branch sounded honestly perplexed, and swiveled his stool around to see if he was missing something behind him.

“That!” she cried, pointing at the movement under his jacket between the shoulder blades. “You have a tentacle! I saw you scratch your ear with it!”

Now Branch started to look angry. “Of course I have a tentacle, what kind of Drazen do you take me for? I’m beginning to see why this stupid hook-up service is free.”

“It’s not free, it’s expensive,” Kelly exploded. “And it set me up with an alien!”

“What are you, some kind of xenophobe?” Branch asked incredulously, as if interspecies dating was the norm in the entire galaxy.

“Xenophobe? Take that back,” Kelly hissed, her green eyes sparking anger of her own. “I’m Earth’s diplomatic liaison to Union Station, and I’ve been working with aliens for…”

“Oh, so everybody who isn’t from your precious Earth is an alien,” Branch interrupted her, and then he stopped and stared at nothing for a moment, as if he was reading from a heads-up holographic display of his own. “Uh, did you say, Earth?”

“Yes, I said Earth. What, are you getting your lame pick-up lines from a teleprompter? Wait, you don’t even speak English, do you? I knew there was something funny about you, but all that facial hair makes it hard to see your lips…” Kelly trailed off, blushing and biting her tongue before she tried to blame it on the light in the bar being poor, or her eyes being tired from overwork.

“English? Why would I speak an archaic language from a strip mining claim?” Branch’s expression showed his frustration at the turn in the conversation. “And why would a world with diplomatic representation on Union Station bargain away mining rights to an entire continent in return for some old Drazen jump ships?”

“A continent?” Her mouth gaped open. “Wait, you work for Belugian?”

“Stakeholder, second class.” Branch drew himself up and looked like he was waiting for a compliment. Kelly’s mind raced as she stalled for time, pouring out every bit of a “My, aren’t you a handsome alien,” vibe she could muster. Negotiations authorized, she said to herself.

“Branch,” Kelly said as she swung her chair toward him, crossed her legs, and repressing a shudder, put her hand on his forearm. “Could I tell you a diplomatic secret without it getting back to Earth where you heard it?”

A strange odor, not unpleasant, filled the air, probably the Drazen way of saying she had his full attention. He looked at her expectantly.

“I shouldn’t be interfering in commercial dealings, of course, but I happen to know that the Belugian contract is invalid,” she cooed, smiling and batting her eyes for good measure.

Branch’s own eyes hardened like olive pits as he swiveled his seat back towards the bar, drained the rest of his Divverflip, and signaled for another. Apparently the schoolgirl approach wasn’t going to buy her anything, but the refill meant he wasn’t planning on getting up and leaving.

“My information shows that the contract was signed and bonded in the presence of a Thark recorder. There can be no question of validity,” he spoke evenly, all of the friendliness gone from his voice.

“I’m well aware of the Thark role in commercial law,” Kelly replied with a light laugh, again playing for time as she hurriedly queried Libby for the entry on Thark recorders. No loopholes there, she’d have to try a shot in the dark. “But what would you say if I told you the party who signed for Earth lacked legal standing?”

Branch’s tentacle reappeared to scratch absently in his thick hair as he toyed with his toxic drink and stared at nothing, obviously exercising his own information implants. Then he turned towards her and said, “Are you going to pretend that the Elected Government of North America isn’t authorized to treat for mineral rights?”

“The Elected Government of North America?” She almost giggled in relief. “That’s a student group. I was in the Senate before my braces were off. It’s just school kids playing at running things,” she concluded and offered Branch a sympathetic smile.

Branch’s eyes unfocused and he tilted his head to one side, leading Kelly to assume he was now conferencing with his colleagues or management. She made use of the time to take a long sip from her screwdriver and to ask Libby to dig through any relevant Earth news about the student government, just to make sure they hadn’t staged a coup in recent years and taken over North America for real. The truth was, the Stryx weren’t the only ones who didn’t take the national governments very seriously anymore.

Back before the Stryx opened Earth, they flooded the existing communications networks with information about the galaxy, bypassing the governmental monopoly on information. After the preparatory period, they delivered advanced technology and off-world transportation on credit, so interstellar trading and human labor exchanges had taken off. Other than collecting taxes when their former citizens were dumb enough to use the banking infrastructure, there just wasn’t much the old governments could do about it.

Whoops, there it was. Libby had found the contract with the Belugians in a student paper under the headline, “Returning Seniors Trade Rocks Rights For Jump Ships.” Damn, the contract language looked pretty serious, and the signees were the elected representatives of over thirty million school kids in a galaxy where some species took the rights of children seriously.

“The penalty clause gives your people the choice of cancelling the contract by paying with labor levies or Yttrium. That’s ten thousand labor years or ten thousand kilograms of Yttrium,” Branch reported after a long pause. “If you can provide me with delivery details, I’m authorized to arrange for the pick-up.”

“Oh, I don’t think that will be necessary,” Kelly answered in her best diplomatic tone. “After all, you must acknowledge that these kids weren’t authorized to negotiate for anybody other than themselves.”

“So they’ll be supplying the labor levies,” Branch continued without missing a beat. “We’d prefer to take the older students, of course, but the younger children could be useful for working in low tunnels underground, not to mention cleaning those hard to reach places between the gears in the mining equipment.”

Kelly furiously skimmed the fine print on her heads-up display, looking for a way to avoid a diplomatic incident without sending ten thousand North American children into virtual slavery for a year. Then she spotted the clause for computing the length of servitude that left the distribution of time over laborers to be determined by the humans. A little quick math and she had her solution.

“Well, I’m not sure how transporting ten million childr

en off Earth for around eight hours is going to make any profit for Belugian, especially after you knock off the time they spend waiting in line to board. But if you insist on enforcing the penalty clause, I suppose their parents will enjoy the free babysitting.”

Branch slammed his drink down on the bar and his tentacle stood out rigidly above his head. Kelly realized that she was looking at one angry Drazen.

“So this is how humans keep their contracts,” he exploded. “You know perfectly well that ten thousand labor years should be in standard ten year commitments. A thousand workers for ten years.”

“I know nothing of the sort, Branch.” Kelly smiled widely and gave a little laugh. “Just as you apparently haven’t heard that on Earth, children have no legal standing to bind themselves by contract.”

“Primitive backwater,” he snorted, his tentacle wilting back over his shoulder. Branch fiddled with his glass, stared off into nothingness for a bit, then grunted. “Look, the truth is that this came to us through some planet chaser working on spec for a finder’s fee. But a deal’s a deal, don’t you agree? We’ve already committed to buy four disintegrator projectors for the job, and they just aren’t much use for anything else. My people think the penalty clause will stand up in Thark Chancery, even if it gets cut back to actual damages. Of course, the litigation will go on for years if you fight, and that will come to much more than the projectors are worth, but there’s a principle at stake here for Belugian. We can’t just start waiving contracts for whoever suffers sellers regret or we’d be out of business, if not at war.”

Kelly hesitated. She didn’t really know if her consulate had a budget for anything beyond keeping the office open. When the need arose, she gave stranded humans small handouts out of her own pocket or raided the petty cash that the consulate generated from the service fees charged to aliens who refused to believe in something for nothing. Neither EarthCent nor Gryph had ever offered a clear answer to her questions about budgeting, they shared a genius for politely changing the subject, but she suspected there were going to be costs involved this time no matter what she decided.

Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16)

Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16) Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18)

Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18) Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4)

Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4) Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11)

Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11) Assisted Living

Assisted Living Con Living

Con Living Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network

Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network Career Night on Union Station

Career Night on Union Station Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15)

Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15) Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9)

Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9) Soup Night on Union Station

Soup Night on Union Station Human Test

Human Test Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4)

Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4) Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12)

Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12) Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10)

Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10) Turing Test

Turing Test Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2)

Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2) Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6)

Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6) Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7)

Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7) Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13)

Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13) LARP Night on Union Station

LARP Night on Union Station Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5)

Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5) LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14)

LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14) Book Night on Union Station

Book Night on Union Station High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3)

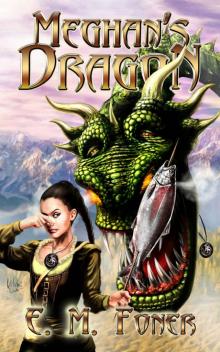

High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3) Meghan's Dragon

Meghan's Dragon Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2)

Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2) Guest Night on Union Station

Guest Night on Union Station Date Night on Union Station

Date Night on Union Station