Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16)

Last Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 16) Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18)

Empire Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 18) Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4)

Space Living (EarthCent Universe Book 4) Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11)

Review Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 11) Assisted Living

Assisted Living Con Living

Con Living Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network

Freelance On The Galactic Tunnel Network Career Night on Union Station

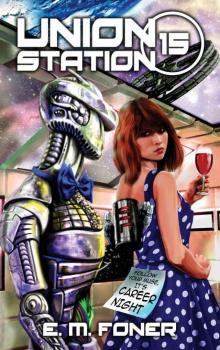

Career Night on Union Station Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15)

Career Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 15) Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9)

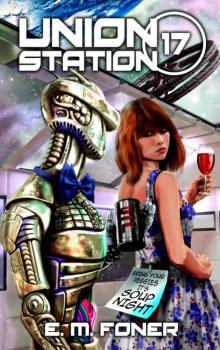

Word Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 9) Soup Night on Union Station

Soup Night on Union Station Human Test

Human Test Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4)

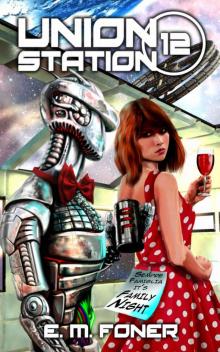

Spy Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 4) Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12)

Family Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 12) Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10)

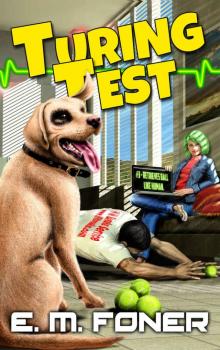

Party Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 10) Turing Test

Turing Test Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2)

Alien Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 2) Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6)

Wanderers On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 6) Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7)

Vacation on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 7) Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13)

Book Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassasor 13) LARP Night on Union Station

LARP Night on Union Station Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5)

Carnival On Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 5) LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14)

LARP Night on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 14) Book Night on Union Station

Book Night on Union Station High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3)

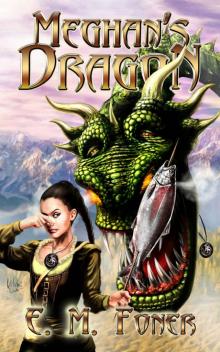

High Priest on Union Station (EarthCent Ambassador Book 3) Meghan's Dragon

Meghan's Dragon Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2)

Human Test (AI Diaries Book 2) Guest Night on Union Station

Guest Night on Union Station Date Night on Union Station

Date Night on Union Station